Every JavaScript environment has a global object. Any variables that are created in the global scope are actually properties of this object, and any functions are methods of it. In a browser environment the global object is the window object, which represents the browser window that contains a web page.

In this article, we’ll cover some important uses of the Window Object:

- The Browser Object Model

- Getting browser information in JavaScript

- Getting and using Browser history

- Creating and controlling windows

- Getting Screen size and display details

This post is adapted from my famous course: JavaScript: Novice to Ninja.

The Browser Object Model

The Browser Object Model (or BOM for short) is a collection of properties and methods that contain information about the browser and computer screen. For example, we can find out which browser is being used to view a page (though, this method is unreliable). We can also find out the dimensions of the screen it is viewed on, and which pages have been visited before the current page. It can also be used for the rather dubious practice of creating pop-up windows, if you’re into annoying your users.

There is no official standard for the BOM, although there are a number of properties and methods that are supported by all the major browsers, making a sort of de facto standard. These properties and methods are made available through the window object. Every browser window, tab, popup, frame, and iframe has a window object.

The BOM Only Makes Sense in a Browser Environment

Remember that JavaScript can be run in different environments. The BOM only makes sense in a browser environment. This means that other environments (such as Node.js) probably won’t have a window object, although they will still have a global object; for example, Node.js has an object called global.

If you don’t know the name of the global object, you can also refer to it using the keyword this in the global scope. The following code provides a quick way of assigning the variable global to the global object:

// from within the global scope

const global = this;Going Global

Global variables are variables that are created without using the const, let or var keywords. Global variables can be accessed in all parts of the program.

Global variables are actual properties of a global object. In a browser environment, the global object is the window object. This means that any global variable created is actually a property of the window object, as can be seen in the example below:

x = 6; // global variable created

>> 6

window.x // same variable can be accessed as a property of the window object

>> 6

// both variables are exactly the samewindow.x === x;

>> trueIn general, you should refer to global variables without using the window object; it’s less typing and your code will be more portable between environments. An exception is if you need to check whether a global variable has been defined. For example, the following code will throw a ReferenceError if x has not been defined:

if (x) {

// do something

}However, if the variable is accessed as a property of the window object, then the code will still work, as window.x will simply return false, meaning the block of code will not be evaluated:

if (window.x) {

// do something

}Some functions we’ve already met, such as parseInt() and isNaN(), are actually methods of the global object, which in a browser environment makes them methods of the window object:

Like variables, it’s customary to omit accessing them through the window object.

Dialogs

There are three functions that produced dialogs in the browsers: alert(), confirm() and prompt(). These are not part of the ECMAScript standard, although all major browsers support them as methods of the window object.

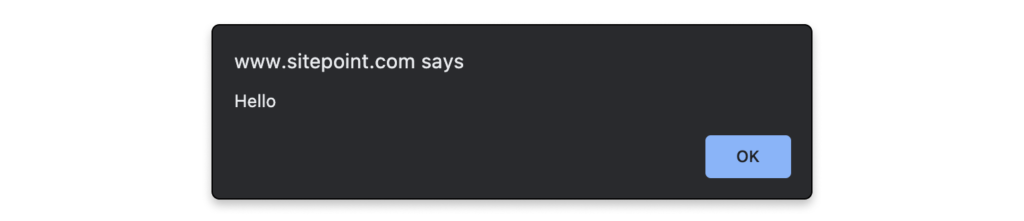

The window.alert() method will pause the execution of the program and display a message in a dialog box. The message is provided as an argument to the method, and undefined is always returned:

window.alert('Hello');

>> undefined

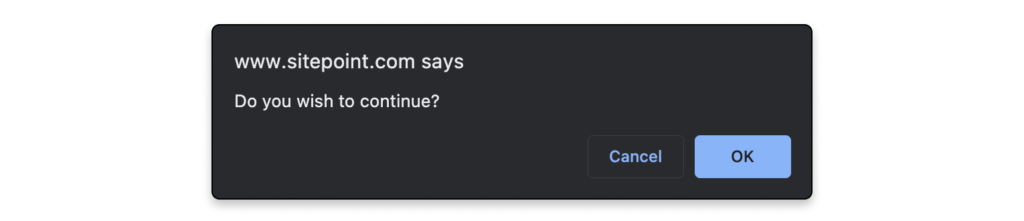

The window.confirm() method will stop the execution of the program and display a confirmation dialog that shows the message provided as an argument, and giving the options of OK or Cancel. It returns the boolean values of true if the user clicks OK, and false if the user clicks Cancel:

window.confirm('Do you wish to continue?');

>> undefined

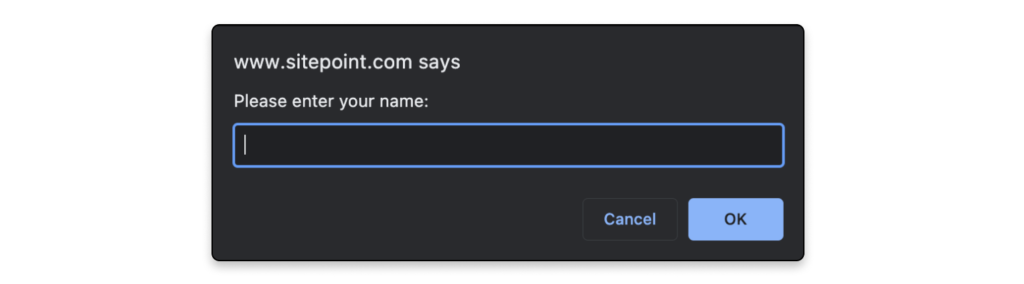

The window.prompt() method will stop the execution of the program. It displays a dialog that shows a message provided as an argument, as well as an input field that allows the user to enter text. This text is then returned as a string when the user clicks OK. If the user clicks Cancel, null is returned:

window.prompt('Please enter your name:');

Use Window Dialogs With Care

It’s worth reiterating again that these methods will stop the execution of a program in its tracks. This means that everything will stop processing at the point the method is called, until the user clicks OK or Cancel. This can cause problems if the program needs to process something else at the same time or the program is waiting for a callback function.

There are some occasions when this functionality can be used as an advantage, for example, a window.confirm() dialog can be used as a final check to see if a user wants to delete a resource. This will stop the program from going ahead and deleting the resource while the user decides what to do.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that most browsers allow users to disable any dialogs from repeatedly appearing, meaning they are not a feature to be relied upon.

Browser Information

The window object has a number of properties and methods that provide information about the user’s browser.

Get Browser information with the Navigator object

The window object has a navigator property that returns a reference to the Navigator object. The Navigator object contains information about the browser being used. Its userAgent property will return information about the browser and operating system being used. For example, if I run the following line of code, it shows that I am using Safari version 10 on Mac OS:

window.navigator.userAgent

>>"Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_12_3) AppleWebKit/602.4.8 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/10.0.3 Safari/602.4.8"Don’t rely on this information though, as it can be modified by a user to masquerade as a different browser. It can also be difficult to make any sense of the string returned, because all browsers pretend to be others to some degree. For example, every browser will include the string “Mozilla” in its userAgent property, for reasons of legacy Netscape compatibility. The userAgent property has been deprecated from the official specification, but it remains well supported in all major browsers.

Get URL details: path, protocol, ports, etc.

The window.location property is an object that contains information about the URL of the current page. It contains a number of properties that provide information about different fragments of the URL.

The href property returns the full URL as a string:

window.location.href

>> "https://www.sitepoint.com/premium/books/javascript-novice-to-ninja-2nd-edition/"This property (as well as most of the others in this section) is a read/write property, which means it can also be changed by assignment. If this is done, the page will be reloaded using the new property. For example, entering the following line into the browser console will redirect the page to the SitePoint homepage:

window.location.href = 'https://www.sitepoint.com/'

>> "https://www.sitepoint.com/"The protocol property returns a string describing the protocol used (such as http, https, pop2, ftp etc.). Note that there is a colon (:) at the end:

window.location.protocol

>> "https:"The host property returns a string describing the domain of the current URL and the port number (this is often omitted if the default port 80 is used):

window.location.host

>> "www.sitepoint.com"The hostname property returns a string describing the domain of the current URL:

window.location.hostname

>> "www.sitepoint.com"The port property returns a string describing the port number, although it will return an empty string if the port is not explicitly stated in the URL:

window.location.port

>> ""The pathname property returns a string of the path that follows the domain:

window.location.pathname

>> "/premium/books/javascript-novice-to-ninja-2nd-edition/"The search property returns a string that starts with a “?” followed by the query string parameters. It returns an empty string if there are no query string parameters. This is what I get when I search for “Darren Jones” on SitePoint:

window.location.search

>> "?q=darren%20jones&firstSearch=true"The hash property returns a string that starts with a “#” followed by the fragment identifier. It returns an empty string if there is no fragment identifier:

window.location.hash

>> ""The origin property returns a string that shows the protocol and domain where the current page originated from. This property is read-only, so cannot be changed:

window.location.origin

>> "https://www.sitepoint.com"The window.location object also has the following methods:

- The

reload()method can be used to force a reload of the current page. If it’s given a parameter oftrue, it will force the browser to reload the page from the server, instead of using a cached page. - The

assign()method can be used to load another resource from a URL provided as a parameter, for example:

window.location.assign('https://www.sitepoint.com/')- The

replace()method is almost the same as theassign()method, except the current page will not be stored in the session history, so the user will be unable to navigate back to it using the back button. - The

toString()method returns a string containing the whole URL:

window.location.toString(); >> "https://www.sitepoint.com/javascript/"

The Browser History

The window.history property can be used to access information about any previously visited pages in the current browser session. Avoid confusing this with the new HTML5 History API. (See http://www.sitepoint.com/javascript-history-pushstate/ post for details.)

The window.history.length property shows how many pages have been visited before arriving at the current page.

The window.history.go() method can be used to go to a specific page, where 0 is the current page:

window.history.go(1); // goes forward 1 page

window.history.go(0); // reloads the current page

window.history.go(-1); // goes back 1 pageThere are also the window.history.forward() and window.history.back() methods that can be used to navigate forwards and backwards by one page respectively, just like using the browser’s forward and back buttons.

Controlling Windows

A new window can be opened using the window.open() method. This takes the URL of the page to be opened as its first parameter, the window title as its second parameter, and a list of attributes as the third parameter. This can also be assigned to a variable, so the window can then be referenced later in the code:

const popup = window.open('https://sitepoint.com','SitePoint','width=700,height=700,resizable=yes');

The close() method can be used to close a window, assuming you have a reference to it:

popup.close();It is also possible to move a window using the window.moveTo() method. This takes two parameters that are the X and Y coordinates of the screen that the window is to be moved to:

window.moveTo(0,0);

// will move the window to the top-left corner of the screenYou can resize a window using the window.resizeTo() method. This takes two parameters that specify the width and height of the resized window’s dimensions:

window.resizeTo(600,400);Annoying Popups

These methods were largely responsible for giving JavaScript a bad name, as they were used for creating annoying pop-up windows that usually contained intrusive advertisements. It’s also a bad idea from a usability standpoint to resize or move a user’s window.

Many browsers block pop-up windows and disallow some of these methods to be called in certain cases. For example, you can’t resize a window if more than one tab is open. You also can’t move or resize a window that wasn’t created using window.open().

It’s rare that it would be sensible to use any of these methods, so think very carefully before using them. There will almost always be a better alternative, and a ninja programmer will endeavor to find it.

Screen Information

The window.screen object contains information about the screen the browser is displayed on. You can find out the height and width of the screen in pixels using the height and width properties respectively:

window.screen.height

>> 1024

window.screen.width

>> 1280The availHeight and availWidth can be used to find the height and width of the screen, excluding any operating system menus:

window.screen.availWidth

>> 1280

window.screen.availHeight

>> 995The colorDepth property can be used to find the color bit depth of the user’s monitor, although there are few use cases for doing this other than collecting user statistics:

window.screen.colorDepth;

>> 24More Useful on Mobile

The Screen object has more uses for mobile devices. It also allows you to do things like turn off the device’s screen, detect a change in its orientation or lock it in a specific orientation.

Use With Care

Many of the methods and properties covered in the previous section were abused in the past for dubious activities such as user-agent sniffing, or detecting screen dimensions to decide whether or not to display certain elements. These practices have (thankfully) now been superseded by better practices, such as media queries and feature detection, which is covered in the next chapter.

The Document Object

Each window object contains a document object. This object has properties and methods that deal with the page that has been loaded into the window. In Chapter 6, we covered the Document Object Model and the properties and methods used to manipulate items on the page. The document object contains a few other methods that are worth looking at.

document.write()

The write() method simply writes a string of text to the page. If a page has already loaded, it will completely replace the current document:

document.write('Hello, world!');This would replace the whole document with the string Hello, world!. It is possible to include HTML in the string and this will become part of the DOM tree. For example, the following piece of code will create an <h1> tag node and a child text node:

document.write('<h1>Hello, world!</h1>');The document.write() method can also be used within a document inside <script> tags to inject a string into the markup. This will not overwrite the rest of the HTML on the page. The following example will place the text "Hello, world!" inside the <h1> tags and the rest of the page will display as normal:

<h1>

<script>document.write("Hello, world!")</script>

</h1>

The use of document.write() is heavily frowned upon as it can only be realistically used by mixing JavaScript within an HTML document. There are still some extremely rare legitimate uses of it, but a ninja programmer will hardly ever need to use it.

FAQs about the JavaScript Window Object

The Window Object in JavaScript represents the browser window or a frame. It serves as the global object for all JavaScript within a browser context.

The Window Object is the global object, so you can access it directly or use the window keyword. For example, window.alert("Hello, World!"); or simply alert("Hello, World!");.

Common properties include window.document for the document object, window.location for the current URL, and window.innerWidth/window.innerHeight for the viewport dimensions.

window.onload event? The window.onload event is triggered when the entire page, including all its assets, has finished loading. It’s commonly used to execute JavaScript code that requires the DOM to be fully loaded.

Yes, you can use the return value of window.open() to check if the pop-up was successfully opened or if it was blocked by the browser’s pop-up blocker.

Darren loves building web apps and coding in JavaScript, Haskell and Ruby. He is the author of Learn to Code using JavaScript, JavaScript: Novice to Ninja and Jump Start Sinatra.He is also the creator of Nanny State, a tiny alternative to React. He can be found on Twitter @daz4126.